black history

From a Time Before Stokely: the Black Power America Needs Today, Tomorrow, and Thereafter /

Knowledge and inspiration for Election Day, November 8, 2016— and every day thereafter:

Fellow East End volunteer Bruce Tarr sent me this December 6, 1919 front page from the Richmond Planet, the city's black newspaper. Recall that 1919 was the year of Red Summer, when a wave of white mob attacks against black people and lynchings swept the country—from Connecticut to San Francisco, and all over the South. No coincidence that this violence happened on the heels of World War I, from which black veterans returned tested and hardened by battle. Many would not willingly bow down to Jim Crow again. When struck, they struck back.

At the end of this bloody year, the Planet, at the time the most outspoken black paper in the South, published a front page drawing by George H. Ben Johnson: BLACK POWER, How Will He Use it? This was half a century before Stokely Carmichael. Johnson and Planet editor John Mitchell weren't talking about identity or symbolism—nothing wrong with that. In fact, this is our focus: how true stories of the black experience build a foundation of knowledge that allow us to feel—to know—that we strong, accomplished, fully American, and so much better than the propaganda that asserts we are less than others.

But this was a straight-up toolbox view of black power—the power of the laborer, the farmer. And the voter. News we can use about tools we have at our disposal. Right now.

It's the Looking That Matters: An Update on the Documentary /

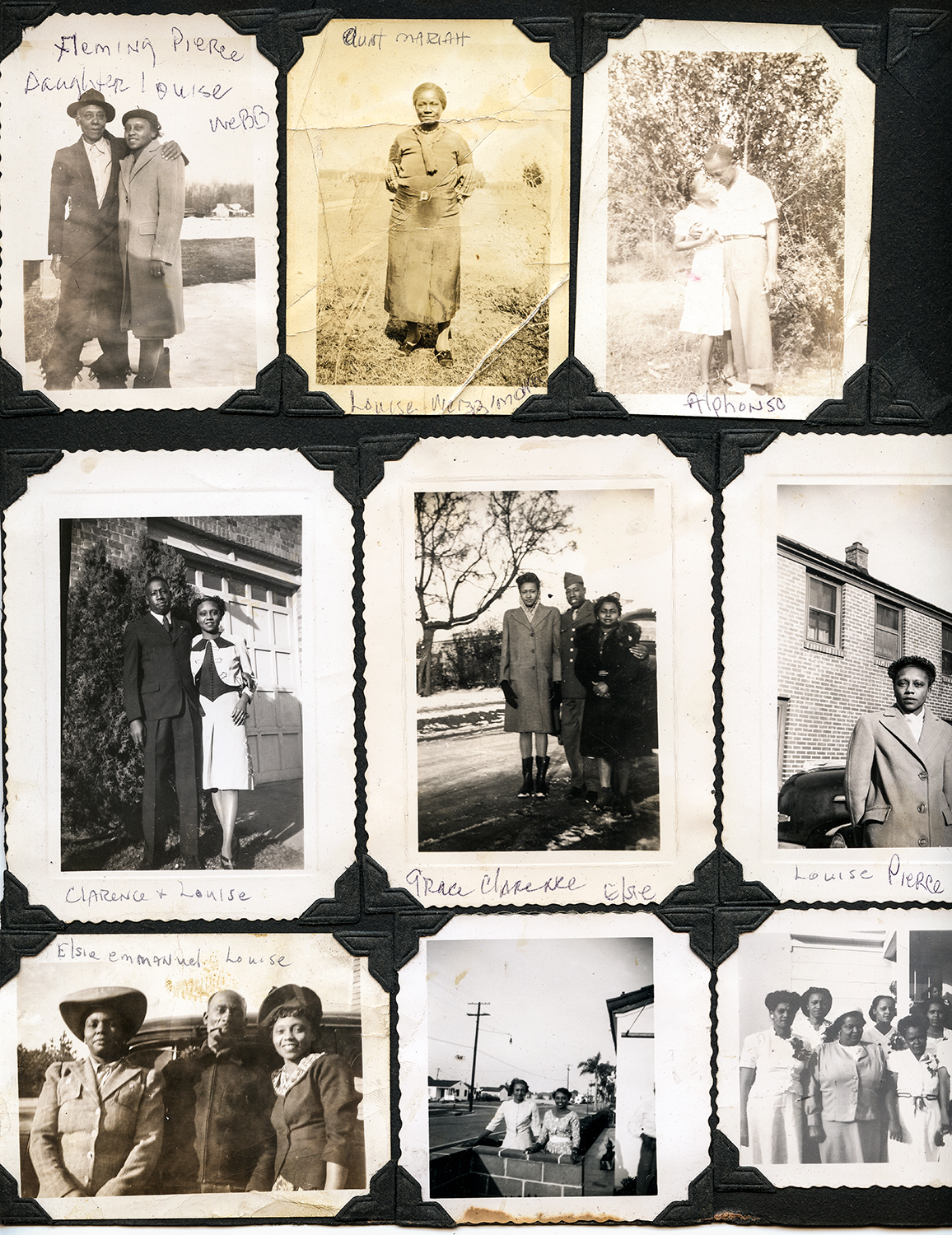

I wonder some days—and almost every night as I try to sleep—if we’ll ever collect enough information and pictures to tell a solid story about Magruder and the everyday pioneers who built it. So much of that history has been erased—or was never recorded.

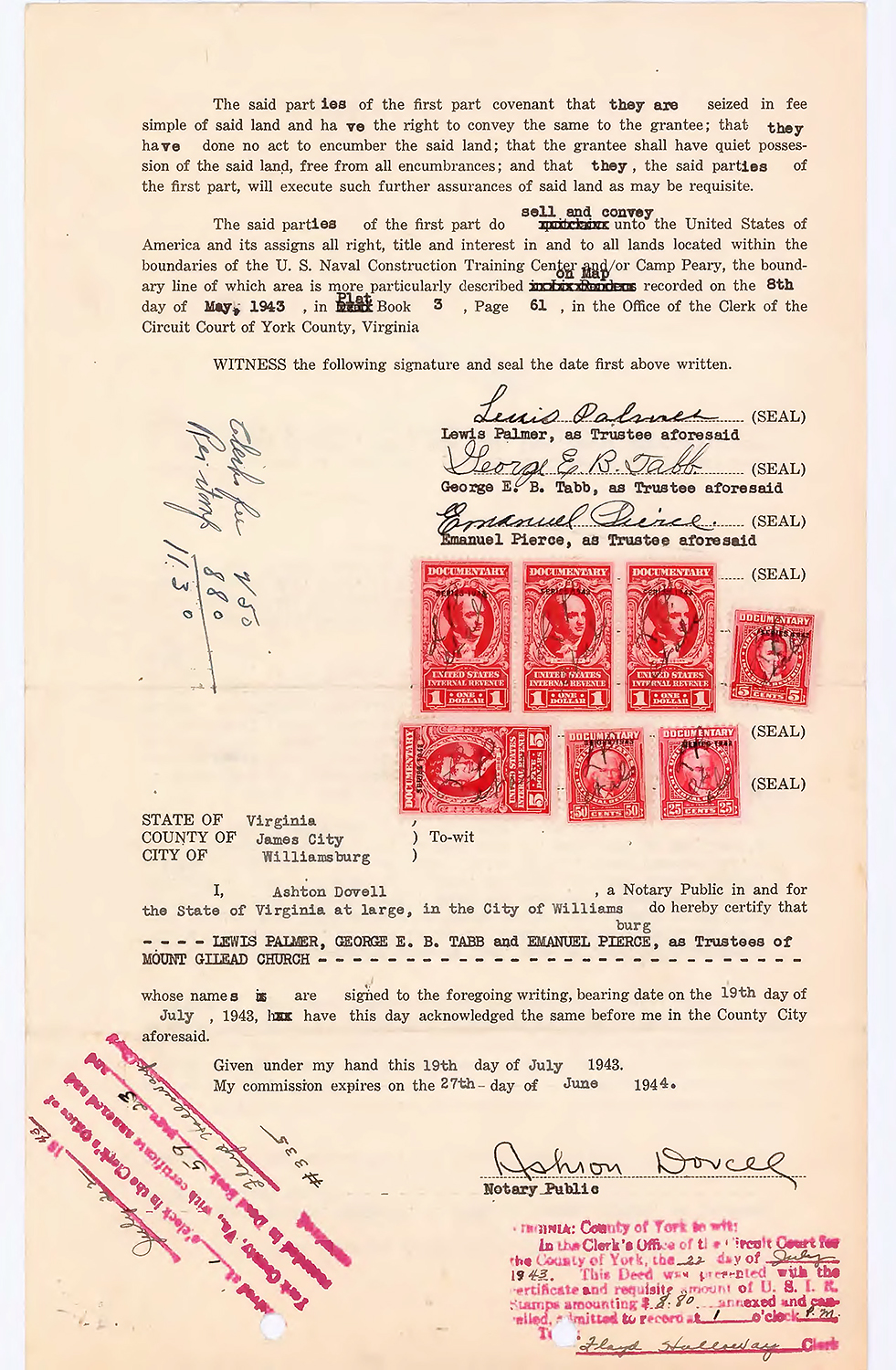

We have found precious pieces of evidence and information in the four years that we’ve been working on Make the Ground Talk. Archivists helped us unearth my great-grandfather Mat Palmer’s Union pension application. From that collection of papers, we gleaned a heap of vital facts, chief among them that Mat had been enslaved and that his last owner was a man named Alexander Maben Hobson.

Our cousin Ann led us to the photo of Mat on the wall of Mt. Pilgrim Baptist Church. Through the Freedom of Information Act, we have obtained government documents relating to the 1942 eviction. At Camp Peary, we visited the graves of Mat and Julia Palmer and other Magruderites at Old Orchard Cemetery.

Scanning her way through thousands of pages, digital and paper, Erin found connections to both sides in the Civil War. We visited the neighborhood where her great-grandparents, descendants of Confederates, lived in Gadsden, Alabama, and found the grave of their (and Erin’s) forebear, “H. M. Stripling Confederate Soldier,” a few counties and one state line east, in Rome, Georgia.

The finding is fantastic. Tracking down each piece of information and visiting each place after months of researching and puzzling, feels wonderful, electric.

For a few moments, we imagine that we’ve cracked the code. Maybe the story will fall into place because we have found this one fragment. And then we settle down.

The finding is rare. Long stretches of nothing—or nothing significant—pass now that we have found the low-hanging fruit, and I gather much of the mid-hanging fruit, too. Digging through archives and attics, poring over microfilm, and poking around cemeteries that just may offer some clues gets old, tedious, frustrating. And although we have found good material, the gaps in the puzzle—of Magruder and the lives of Mat and Julia Palmer—are still larger than the collection of pieces that we have assembled.

Massive questions remain. There is little trace of Julia in the historical record. There are maddening holes in Mat’s story—among them, what made him choose to settle in York County, Virginia, after serving in the Civil War? When did he live in Richmond, as his Union pension application says he did? Why do facts about the “Mathew Palmer” living in Richmond who we find in the census not match up with what we know about our Mat? What have we got wrong? And what have we got right?

In doing all of this hunting and pecking, we have learned a lot about ourselves, about history—Virginian, African American, American—and we have found that others are searching along the same lines. And we have learned one lesson that now sustains us: It’s the looking that matters.

The looking—the process of researching, visiting, interviewing—itself strengthens and affirms our faith in the power of our past and in the people whose stories we’re telling. And we have become part of a diverse and diffuse community of searchers, amateur and professional, gathering textual and physical fragments that allow us to tell truer stories of the American past.

All this to say that our looking goes on and will continue for at least another couple of years. We are assembling the pieces of the documentary film, slowly, with guidance from our advisers, family, and friends. I can’t say when the doc will be complete. I have tried this before and been very wrong. But I will say that we have left Brooklyn and bought a house in Richmond, in Church Hill, where we have rented for two years. We’re committed to this project, to this process, the people and history we are researching, and our new friends, colleagues, and neighbors. We’ll be sending out periodic updates such as this one to give people a better sense of our progress. —BP

Summering at the Cemetery /

We've been back in Virginia full-time since Memorial Day weekend, settling into our RVA rhythm after four-plus months in New York. We never expected to be Richmonders, but we're increasingly at home here—returning felt right. A big part of that is our work at East End Cemetery, which has connected us to people, places, and history we might never have known.

And so much has happened since we've been back! Seemingly out of the blue, the Virginia Outdoors Foundation, a state-chartered agency, awarded East End and neighboring Evergreen a $400,000 grant—seed money for their preservation in perpetuity. The following week, VA Governor Terry McAuliffe made a statement at the cemetery in support of the grant. That was a surreal moment. (When a fellow volunteer asked Thomas Taylor, who has maintained his family's plot for decades, whether he ever thought a sitting governor would visit East End, he said, with a wry laugh and not a moment's hesitation, "Only if he was being buried here.")

On the same day McAuliffe came, a mini-herd of goats from Bright Hope Farm & Apiary arrived on the scene, part of a trial to see whether the voracious nibblers can help us tame some of the rampant overgrowth that still obscures much of the cemetery. Over the course of several days, other goats were cycled in and managed to pack away a goodly patch of greenery.

Meanwhile, we've continued our documentation of the cleanup effort. Buzzfeed recently published a gallery of Brian's photographs with a piece he wrote about recent developments at East End. It's hovering around 100K views—so keep clicking!